THE AI IMPOSSIBLE TRINITY

Why America Cannot Simultaneously Win the Compute Race, Stabilize Its Bond Market, and Preserve Monetary Independence—And What Happens When the System Breaks

A Strategic Intelligence Briefing for December 2025

By Shanaka Anslem Perera

15th December 2025

“The impossible trinity teaches us that you can have any two of three things, but never all three. The question is not whether the system breaks, but which leg gives way first.”

— Adapted from Robert Mundell’s Nobel Lecture, 1999

THE COLLISION THAT WALL STREET REFUSES TO SEE

Something unprecedented is unfolding in the architecture of American capitalism, and the consensus has catastrophically misread it.

The prevailing narrative—repeated with religious conviction across Bloomberg terminals, Federal Reserve research papers, and McKinsey strategy decks—holds that the artificial intelligence revolution represents a deflationary productivity miracle. In this telling, AI will compress costs, accelerate output, and resolve the fiscal contradictions that have haunted American policymakers since the 2008 financial crisis. The technology titans spending hundreds of billions on GPU clusters and data centers are not creating systemic risk; they are building the infrastructure for a new golden age of American competitiveness.

This narrative is not merely wrong. It is dangerously incomplete in ways that will become apparent only when the contradictions it ignores can no longer be suppressed.

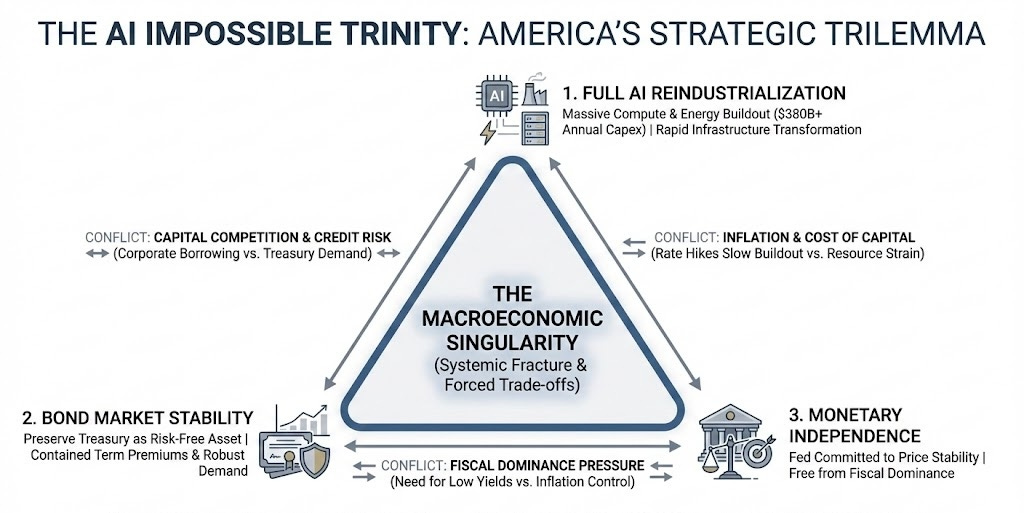

The United States has entered what can only be described as a macroeconomic singularity—a collision point where the capital, energy, and institutional requirements of the AI infrastructure buildout have smashed into the finite capacity of the physical and financial worlds. At the center of this collision sits what I term AI’s Impossible Trinity: three strategic objectives that America is attempting to achieve simultaneously, despite their fundamental mutual exclusion.

The first objective is Full AI Reindustrialization—the rapid construction of sovereign-grade AI infrastructure, requiring capital expenditures now exceeding $380 billion annually from the hyperscalers alone, demanding a transformation of the American electrical grid not seen since rural electrification, and consuming resources at a pace that makes the Manhattan Project look like a rounding error.

The second objective is Bond Market Stability—the preservation of the U.S. Treasury market as the world’s risk-free asset, characterized by contained term premiums, robust foreign demand, and the continued functioning of the dollar as the gravitational center of global finance.

The third objective is Monetary Independence—the maintenance of a Federal Reserve committed to price stability and free from the gravitational pull of fiscal dominance, where monetary policy serves economic stabilization rather than government debt management.

The evidence accumulated through 2025 demonstrates that this trinity is untenable. America can achieve any two of these objectives, but not all three. The sheer magnitude of corporate borrowing required to fund the compute arms race is transforming the credit landscape. The physical constraints of the power grid are generating localized inflation that threatens price stability. And the institutional framework designed to maintain monetary independence is straining under pressures it was never designed to withstand.

What follows is not a prediction of collapse. It is something more nuanced and, ultimately, more useful: a mapping of the pressure points where the impossible trinity is already beginning to fracture, an honest assessment of what consensus analysis has gotten wrong, and a framework for understanding which leg of the trinity will ultimately give way.

PART I: THE CAPEX SUPERCYCLE AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF BIG TECH

From Cash Fortresses to Debt Engines

For nearly a decade, the hyperscalers—Alphabet, Amazon, Meta, Microsoft—operated with what analysts termed “fortress balance sheets.” These companies accumulated cash hoards measured in hundreds of billions, maintained minimal debt, and funded their growth primarily through operating cash flows. The tech giants of the 2010s were, in financial terms, the most conservative major corporations in American history.

That era ended definitively in 2025.

The arithmetic is unforgiving. Microsoft spent $35 billion in the third quarter of 2025 alone on capital expenditures—more than many Fortune 500 companies generate in annual revenue. Amazon deployed $36 billion. Alphabet invested $24 billion. Meta contributed $19 billion. Collectively, the Big Four hyperscalers are now spending at an annualized rate approaching $460 billion, with consensus estimates for 2026 pushing toward $500-600 billion.

These figures demand context. The entire U.S. defense budget—the largest military expenditure in human history—runs approximately $886 billion annually. The hyperscalers are now spending more than half that amount on data centers, GPU clusters, and the infrastructure required to train and deploy foundation models. The AI buildout has become, in purely financial terms, the largest private infrastructure project in human history.

The cash flows from legacy businesses—search advertising, cloud services, social media, e-commerce—cannot fund this expenditure without compromising the shareholder returns that maintain market capitalizations. The solution has been a synchronized pivot toward aggressive debt issuance that has fundamentally altered the landscape of investment-grade credit markets.

Consider the magnitude: U.S. investment-grade technology bond issuance reached $211 billion in 2025—a 115 percent increase from the prior year. Meta’s $30 billion October offering attracted a $125 billion order book, demonstrating demand so overwhelming that the company could have sold four times its intended amount. Alphabet followed with a $25 billion issuance in November. Oracle’s $18 billion September deal included a rare 40-year tranche, locking in capital for nearly half a century to fund infrastructure with a useful life measured in years.

This last detail reveals a critical vulnerability that few have examined. The physical shell of a data center may last four decades. The silicon inside—the GPUs that represent the actual value driver—depreciates on cycles of three to five years as Moore’s Law successors continue their relentless march. Companies are issuing 40-year debt to fund assets with effective economic lives shorter than a presidential term. The mismatch between financing duration and asset utility represents a structural fragility that will only become apparent when the refinancing cycle arrives.

The “Neocloud” Vulnerability: When GPUs Become Subprime Collateral

While the hyperscalers possess the cash flows to service their expanding debt, a secondary tier of actors presents risks that rhyme uncomfortably with 2007.

Companies like CoreWeave, Lambda, and Crusoe have built businesses on a model that would have been recognized instantly by anyone who lived through the subprime mortgage crisis: borrow against assets whose value depends on assumptions that may not hold, then borrow more against the appreciated collateral, creating a reflexive loop that works magnificently until it doesn’t.

In the neocloud model, the collateral is not housing but graphics processing units. These companies have engaged in aggressive asset-backed lending where the security is the GPU itself—specifically, the assumption that the resale value and rental yield of an Nvidia H100 will remain stable over the term of the loan.

This assumption is already being tested. CoreWeave triggered administrative defaults on its $7.6 billion Blackstone facility in late 2024 when it transferred funds to foreign subsidiaries for GPU purchases, violating U.S.-only collateral requirements. Blackstone waived the defaults—for now. But HSBC has initiated coverage of CoreWeave with a “Reduce” rating, warning explicitly of covenant breach risks. The company’s March 2025 IPO at $40 per share and subsequent rise to $90 masks underlying leverage that becomes problematic if GPU rental rates compress faster than debt service requirements.

The mechanism of fragility is circular and familiar. Neoclouds borrow to buy GPUs. The “book value” of these GPUs secures further loans. As Nvidia releases more powerful architectures—Blackwell, then Rubin—the rental rate for older chips collapses. The loan-to-value ratio spikes, triggering margin calls or covenant breaches. If a major neocloud faces liquidation, the flooding of thousands of used H100s into the secondary market would crash collateral values across the entire sector.

Private credit funds have reportedly allocated nearly 20 percent of their deal financing to such structures. This is not systemic in the way that subprime mortgages were systemic—the absolute numbers are smaller, and the interconnections less dense. But it represents a pocket of concentrated risk that consensus analysis has largely ignored, and it provides a transmission mechanism through which AI investment enthusiasm could transform into credit stress.

PART II: THE BOND MARKET PARADOX—WHY THE PREDICTED CRISIS HASN’T ARRIVED (YET)

The Predictions That Failed

Intellectual honesty requires acknowledging what the crisis narrative got wrong in 2025.

The prediction that Treasury yields would exceed 5 percent on a sustained basis failed to materialize. The 10-year yield peaked around 4.5 percent and currently trades near 4.19 percent—elevated by historical standards but nowhere near the crisis threshold. The prediction that investment-grade corporate spreads would widen by 30 to 50 basis points proved not merely wrong but spectacularly inverted: spreads compressed to 72 basis points in September 2025, their tightest level since 1988, and remain near 80 basis points as the year closes.

The prediction that the Federal Reserve would begin discussing yield curve control also failed. The August 2025 framework review examined foreign YCC experiences in an academic context but concluded explicitly that “expanding the toolkit has not been a recent focus.” No FOMC minutes, speeches, or official communications indicate active consideration of rate caps for the United States.

These failures demand explanation, not dismissal.

The Absorption Miracle: How Markets Digested Record Issuance

The bond market’s resilience in 2025 represents one of the most remarkable absorption events in financial history. First-quarter investment-grade issuance reached $585 billion—a record—yet spreads tightened rather than widened. September saw $57 billion in high-yield issuance, the third-strongest month ever, yet compression continued.

Three factors explain this apparent paradox.