THE ENERGY SINGULARITY

How AI’s Insatiable Power Hunger Is Triggering a Nuclear Renaissance and Creating the Definitive Second-Order Trade of the Decade

Institutional Research | 30 December 2025

By Shanaka Anslem Perera

I. THE CONFESSION BURIED IN THE GRID

On December 17, 2025, the largest power grid in America confessed something it desperately hoped would remain buried in the arcane language of capacity auction results.

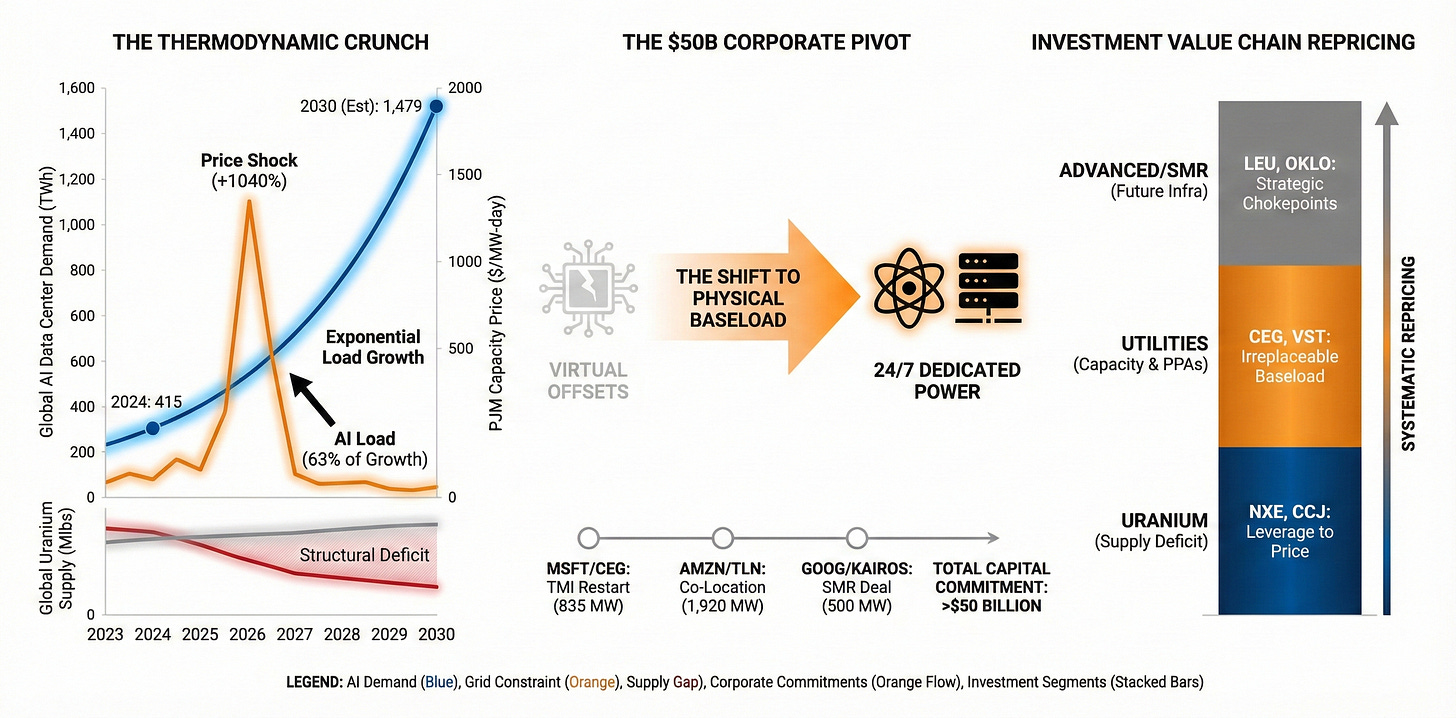

PJM Interconnection, the regional transmission organization serving thirteen states and 65 million people from Illinois to New Jersey, released the results of its Base Residual Auction for the 2027/2028 delivery year. The headline number was so extreme that multiple trading desks initially assumed a data error: $333.44 per megawatt-day, hitting the price cap and representing a 1,040% increase from just two years prior.

But buried in the supplementary materials was an even more revealing figure. Data centers alone accounted for 63% of the incremental load growth driving this price explosion.

The arithmetic was merciless. A single organization’s insatiable appetite for electricity had broken the fundamental economics of the nation’s most important power market. The culprit was not industrial expansion. It was not population growth. It was not electrification of transportation.

It was artificial intelligence.

This is not a story about utilities. This is not even primarily a story about nuclear energy. This is a story about the physical limits of computation colliding with the thermodynamic reality of the American electrical grid, a collision that is forcing the most capital-rich companies in human history to bid astronomical premiums for a resource that, until twenty-four months ago, was priced like a commodity.

And it is creating what may be the most asymmetric investment opportunity of this decade: the systematic repricing of baseload power from a utility product to critical AI infrastructure.

The evidence is no longer speculative. Microsoft signed a twenty-year power purchase agreement with Constellation Energy to restart the Three Mile Island nuclear reactor at an estimated price exceeding $100 per megawatt-hour, roughly double the prevailing wholesale rate. Amazon committed $18 billion over two decades for power from Talen Energy’s Susquehanna nuclear plant. Meta secured the entire output of Constellation’s Clinton nuclear facility. Google signed the first-ever corporate agreement for multiple small modular reactors.

In aggregate, technology companies have committed more than $50 billion to nuclear power in the past eighteen months alone.

The question is no longer whether this shift is happening. The question is whether the market has correctly priced its magnitude, duration, and second-order effects.

Our analysis suggests it has not.

II. THE PHYSICS OF INTELLIGENCE

To understand why nuclear energy is becoming indispensable to artificial intelligence, one must first understand why AI is fundamentally an energy problem masquerading as a software problem.

The relationship between computational power and energy consumption is governed by the immutable laws of thermodynamics. As silicon transistors shrink and switch at higher frequencies, heat dissipation rises non-linearly. The advent of the Transformer architecture and the subsequent explosion of generative AI has accelerated this consumption curve beyond any trajectory that historical infrastructure planning anticipated.

A single query to ChatGPT consumes approximately 2.9 watt-hours of electricity. This is roughly ten times the energy required for a traditional Google search. Extrapolate this across billions of daily interactions, add the continuous workloads of model training, and the energy delta becomes staggering.

The International Energy Agency projects that global data center electricity consumption will double from 415 terawatt-hours in 2024 to 945 terawatt-hours by 2030, accounting for nearly half of U.S. electricity demand growth during that period. Goldman Sachs research suggests even higher figures, projecting data center power demand to reach 1,479 terawatt-hours by 2030.

But aggregate projections obscure the true nature of the crisis.

Data centers are not evenly distributed. They cluster to minimize latency and maximize interconnectivity. In Northern Virginia’s Data Center Alley, which processes a significant portion of global internet traffic, data center load already dwarfs residential and commercial demand. The local grid cannot add transmission capacity overnight. Permitting and construction for high-voltage transmission takes seven to ten years. AI deployment operates on cycles of eighteen to twenty-four months.

This temporal mismatch creates what we term the capacity gap: a structural shortage that cannot be resolved by building new wind farms in remote locations because the transmission infrastructure to deliver that power does not exist.

The hyperscalers require what the industry calls five-nines reliability: 99.999% uptime. An AI training cluster costing upwards of five billion dollars to construct, equipped with hundreds of thousands of NVIDIA GPUs, cannot tolerate power interruptions. The opportunity cost of idling such infrastructure due to low wind speeds or cloud cover is astronomical.

To power a one-gigawatt data center with solar alone would require building three to four gigawatts of solar capacity to account for capacity factor, plus a massive battery array to bridge overnight gaps. The levelized cost of electricity for such a firm renewable system remains prohibitively expensive compared to baseload generation.

Nuclear energy stands alone as the only scalable, carbon-free, dispatchable baseload power source capable of meeting the technology sector’s dual mandates of reliability and net-zero emissions.

Existing nuclear reactors operate at capacity factors exceeding 92%, meaning they run at full power nearly all the time regardless of weather. They are carbon-free. They are dense: a single nuclear plant generates the same output as a solar farm thousands of times its physical footprint.

For hyperscalers racing to dominate artificial intelligence, nuclear is not merely one option among many. It is the only option that satisfies all constraints simultaneously.

III. THE DEALS THAT CHANGED EVERYTHING

The pivot from financial offsets to physical power represents a fundamental reconception of how technology companies secure energy.

For years, hyperscalers achieved their “100% renewable” goals through the purchase of Renewable Energy Credits and virtual Power Purchase Agreements. In a virtual PPA, a technology company agrees to buy power from a wind farm in Texas at a fixed price while simultaneously consuming power from the grid in Virginia, netting out the financial transaction and claiming the green attribute.

This financial engineering created favorable optics while solving nothing about physical delivery.

A wind farm in Texas does not physically keep the lights on in a Virginia data center. As grid constraints intensified, hyperscalers recognized that virtual green power is insufficient for actual operational requirements. They need physical green power generated at the same time and place as consumption.

This realization triggered the rush toward what the industry calls 24/7 Carbon-Free Energy goals. Nuclear energy is the only technology that fits this specific profile at scale.

The Microsoft-Constellation Deal: A Template for the New Paradigm

In September 2024, Microsoft signed a twenty-year power purchase agreement with Constellation Energy to restart Three Mile Island Unit-1. The reactor, which operated safely and efficiently for decades before being retired in 2019 for economic reasons, will be refurbished and brought back online as the Crane Clean Energy Center.

Microsoft will purchase one hundred percent of the plant’s 835-megawatt output.

This is not a minor financial arrangement. Industry analysts estimate Microsoft is paying north of $100 per megawatt-hour for this power, roughly double the prevailing wholesale rate. The willingness to pay such a premium confirms a fundamental truth: for hyperscalers, the price of power is secondary to its availability and cleanliness.

No U.S. reactor retired for economic reasons has ever been brought back online. Microsoft’s willingness to fund this unprecedented restart validated the nuclear premium thesis and catalyzed a cascade of similar announcements.

The Amazon-Talen Arrangement: Co-Location as Strategic Asset

Amazon’s arrangement with Talen Energy pushes the model even further. Rather than simply buying power delivered through the grid, Amazon purchased land adjacent to Talen’s Susquehanna nuclear plant for $650 million and is constructing a data center campus that will draw power directly from the reactor behind the meter.

This co-location bypasses transmission charges and ensures that AWS data centers receive uninterrupted nuclear power regardless of grid conditions elsewhere. The full agreement, valued at approximately $18 billion over its duration, will eventually provide up to 1,920 megawatts of dedicated capacity.

The strategic intent is unmistakable: transform the Susquehanna nuclear complex into an AI campus where reactor and servers sit side by side, a template that could be replicated across every nuclear facility in America.

Meta, Google, and the Proliferation of Nuclear PPAs

Meta followed with a twenty-year agreement for the entire output of Constellation’s Clinton nuclear plant in Illinois, securing 1,121 megawatts starting in June 2027.

Google took a different approach, signing the first-ever corporate agreement for multiple small modular reactors with Kairos Power, committing to purchase 500 megawatts from six to seven SMRs beginning around 2030. The Tennessee Valley Authority partnership for Kairos’s 50-megawatt Hermes 2 demonstration plant accelerates the deployment timeline.

What these deals share is a willingness to pay substantial premiums for guaranteed, carbon-free, round-the-clock power. This willingness represents the monetization of nuclear’s unique attributes: reliability and density.

It transforms nuclear plants from commodity power producers into strategic infrastructure assets, comparable in function to data center real estate or submarine fiber-optic cables.

The market has only begun to price this transformation.

IV. THE REGULATORY BATTLEFIELD

Before examining specific investment opportunities, one must understand the regulatory environment that currently governs the speed and profitability of the nuclear renaissance.

The concept of co-location, building a data center directly connected to a power plant to bypass the transmission grid, has ignited fierce conflict within the U.S. electricity sector.

The Cost Allocation Dispute

The central conflict concerns cost allocation. In a standard arrangement, a power plant injects electricity into the grid, and a consumer draws electricity from the grid, both paying transmission fees that support shared infrastructure.

In a co-located, behind-the-meter arrangement, the consumer draws power directly from the generator before it reaches the wider grid.

Proponents, primarily the unregulated Independent Power Producers and technology giants, argue this relieves congestion and represents efficient market behavior. By using power onsite, they relieve strain on the transmission grid and should not be forced to pay transmission fees for infrastructure they do not use.

Opponents, primarily regulated utilities that own transmission infrastructure, argue this constitutes free-riding. They contend that co-located data centers still rely on the grid for backup services during planned or unplanned outages. If these massive loads stop paying transmission fees, the cost of maintaining the grid shifts to other ratepayers: residential households and small businesses.

This is the political third rail of cost-shifting.

The FERC Rejection: Initial Interpretation Was Wrong

In November 2024, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission rejected an amended interconnection service agreement between PJM, Talen Energy, and Amazon that would have increased the co-located load allowance at Susquehanna from 300 to 480 megawatts.

The market initially interpreted this as a blow to the nuclear data center thesis, triggering selloffs in Constellation and Vistra shares.

This interpretation was incorrect.

The rejection addressed specific deficiencies in PJM’s filing regarding cost allocation and potential shifting of approximately $140 million annually to other ratepayers. FERC did not ban co-location. It demanded a standardized framework.

Chairman Phillips’s dissent explicitly warned that blocking such innovations “creates a national security risk” by slowing AI infrastructure deployment.

The December 2025 Order: The Green Light

On December 18, 2025, FERC issued a superseding order directing PJM to establish transparent rules for co-located loads.

The order created three new transmission service options:

First, interim non-firm service allowing data centers to connect immediately while grid upgrades proceed. This solves the timing mismatch. Data centers can connect now, relying on backup generation or load throttling during emergencies, while slow grid upgrades proceed. This preserves the speed-to-market premium.

Second, firm contract demand service allowing reservation of specific capacity slices. This is a novel, bespoke asset class. It allows a data center to pay for a grid insurance policy without being treated as a full network load for costs they do not cause. It explicitly allows for the load to be served primarily by the co-located generator while maintaining a firm link to the grid for backup.

Third, non-firm contract demand service providing flexibility for interruptible loads.

The Strategic Implication: Regulatory Moat Creation

The December Order effectively legitimizes co-location while mandating that hyperscalers pay for the option to use grid backup services.

By standardizing these services, FERC has raised the barrier to entry. Navigating complex transmission studies requires sophisticated trading operations and substantial balance sheets. This regulatory framework favors large fleet operators like Constellation and Vistra over smaller, single-asset merchant plants.

Hyperscalers will gravitate toward incumbents who can package firm contract demand service with multi-gigawatt PPAs, paying premium prices for regulatory certainty.

The market sees regulatory risk. We see regulatory moat creation.

V. THE URANIUM SUPPLY CRISIS

The nuclear renaissance is meeting a mining depression. Years of underinvestment have left the uranium supply chain brittle, and 2025 exposed the cracks with devastating clarity.

The market is entering a period of structural deficit that cannot be resolved by short-term price signals alone.

The Production Shortfall

Global uranium mine production of approximately 130 to 145 million pounds annually falls 30 to 50 million pounds short of the roughly 180 million pounds required by existing reactors. This deficit does not account for 63 to 70 reactors currently under construction worldwide, including 32 in China alone.

Secondary supplies from utility inventories and enricher tails re-enrichment continue declining. Primary production now covers 90% of requirements compared to 78% in 2022. The market is eating its seed corn.

The McArthur River Shock

Cameco’s announcement regarding production delays at McArthur River and Key Lake sent shockwaves through the market.

Transitioning to new mining zones in the Athabasca Basin requires freezing the ground to minus forty degrees Celsius to prevent water inflow. This is technically perilous and slow. The reduction of 2025 guidance from 18 million to 14-15 million pounds removes tier-one supply from a market already in structural deficit.

To fulfill its contracts, Cameco is forced to enter the spot market to buy uranium. The world’s second-largest producer has become a net consumer of inventory, placing a high floor under spot prices.

The Russian Ban and Enrichment Bottleneck

The Prohibiting Russian Uranium Imports Act created a hard separation between Western enrichment capacity and the Rosatom sphere. The Western world effectively cut itself off from the dominant historical supplier of enriched uranium.

Centrus Energy is the only U.S.-licensed entity for High-Assay Low-Enriched Uranium production, required for next-generation reactors. Their demonstration facility in Piketon, Ohio delivered 920 kilograms to the Department of Energy in 2025, validating technical capability but at production volumes far below commercial requirements.

Because enrichment capacity is the bottleneck, enrichers are overfeeding their centrifuges: using more natural uranium to produce the same amount of enriched uranium in less time. This creates additional demand for natural uranium, estimated at 20-30 million pounds per year globally. This secondary demand driver is often ignored in simple supply-demand models but is critical in a tight enrichment market.

The Contracting Panic

Utility contracting behavior confirms the severity of the supply situation.

Coverage gaps of 25-30% for 2025 requirements expand to 35-40% for 2026 and approximately 70% by 2027-28. Long-term contract prices reached $86 per pound in late 2025, a seventeen-year high.

The incentive price for new mine development has risen to $80-100 per pound minimum, with some analysts citing $100-150 as necessary for greenfield projects.